Tapering for Performance: A Quick “How To” Guide

By: Andy Galpin, Ph.D., CSCS*D, NSCA-CPT*D

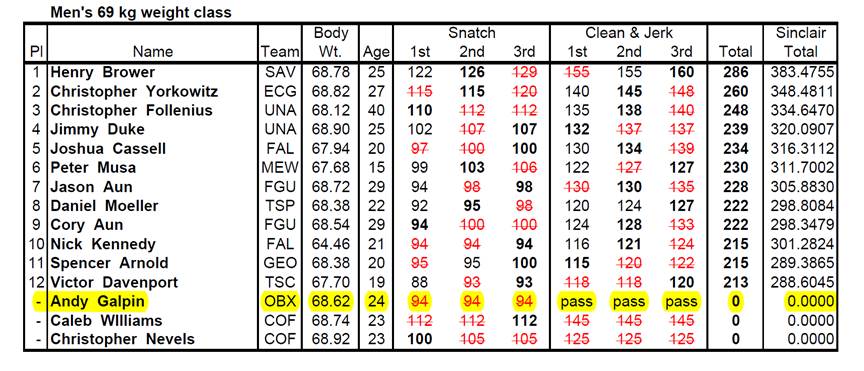

I will never forget the morning of November 22nd, 2007. I remember the color of the carpet in rented bedroom. I remember the smell of my roommates’ percolating French press. This is seared into my synapses because on that day, I reached a physical peak. My technique was perfect. I was strong, crisp, and fast under the bar. Eight days later, I missed all 3 of my Snatch attempts (with a weight ~15% less) at the American Open Weightlifting Meet:

I had to completely pass the clean and jerk attempts because I couldn’t even deadlift my openers. I peaked too early. You may have experienced the other side of a FUBAR’d training plan. It looks something like this: bomb competition, take a week or two off, come back and set a PR. This is a classic example of overtraining. If you’ve played sports or ran enough races, you’ve experienced one of these two “miss-timed peaks”, or both. Peaking (or “tapering”) for completion is critical, but often blatantly ignored or simply misunderstood. The following is a breakdown of the scientific basis for taper and a guide to help you understand what to do and how to do it!

What Physiologically Causes Overtraining?

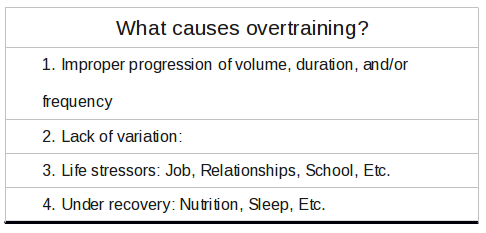

Convincing your body to change its physical capacity requires serious convincing. Consistent stress provides the impetus for adaptation. However, the actual adaptation occurs during recovery. Herein lies our conundrum: how to I maximize my stimulus for adaptation while allowing enough time for adaptation? Too much stress = overtraining. Too little stress = no physiological need to adapt. In other words, Performance = Fitness – Fatigue. Overtraining is simply a mismanagement of the stress/recovery continuum in a manner which: a) attempts to improve fitness solely through increased training-induced stress, b) fails to sufficiently reduce fatigue, or both (a+b). A properly executed taper allows maximal stress and recovery by strategically planning when to emphasize each.

Fitness (aka conditioning, endurance, VO2max, etc.) is physiology quite stable; fatigue, however, changes rapidly. For example, 7 hard days of training or 7 days of sitting on the beach will both result in virtually no change in your VO2max or best 5k time. On the other hand, sleep 5 hours tonight. Then 12 hours tomorrow. Fatigue is transient. When we apply this understanding to taper we should realize that reducing training volume won’t compromise fitness, but will quickly eliminate fatigue.

How To Taper

Like all things in the biological world, major person to person variations exist in taper strategy. The following are general guidelines and should function as a starting place.

Volume

The available evidence suggests reductions in training volume by ~40-90% do NOT reduce fitness levels, depending on preceding training. 90% might be excessive. Most athletes do well ~50%. Be careful with frequency, though. An athlete used to training 6x/week will feel terrible if reduced to 3 workouts per week. Find a way to cut volume while preserving ~75% of the frequency. If you train 6 times per week, don’t go to less than 4. If you have 10 workouts per week, don’t drop below ~6-7. You can also experiment with your rate of volume reduction. Mujika & Padilla (MSSE, 2003) show clear evidence that multiple methods are effective. For example, you may choose to reduce volume by 50% (“step taper”) starting on day 1 of the taper. Another approach would be to gradually reduce volume, hitting a 50% reduction over the course of the entire taper (“linear taper”). This is personal preference.

Recommendations = ~40-60% drop in volume

Intensity

Intensity is RARELY a cause of overtraining/fatigue (remember, it’s almost always a volume issue), so reducing it won’t reduce fatigue. Moreover, Speed, power, strength, and/or maximal aerobic capacity (i.e., VO2max) are often the most significant factors separating winners vs. losers. You don’t want to go into a competition having not gone hard in a while.

Recommendation: ↔ or ↑ intensity during taper.

Duration

While fitness is stable, it’s not everlasting. Too short of a taper doesn’t adequately remove fatigue. Too long will cause you to loose fitness. Thus, the length or duration of the taper depends on how long you’ve been training. A 2 week taper isn’t needed if you’ve only trained 2 weeks for the competition. A good rule is 1-2 day of taper per month of training (but this is variable). The minimum is 4 days, with athletes often needing up to 21 days. Most will likely fit in the 6-14 day range.

Recommendation: 6-14 days.

Proof It Works

The study:

Several years ago I had the unique opportunity to test this strategy with a College Cross Country team (Luden, JAP, 2011). We performed full physiological and performance profiles (including muscle biopsies) at 1) the start of the season, and 2) before, and 3) after a 3 week taper (leading up to Conference Championships).

Several years ago I had the unique opportunity to test this strategy with a College Cross Country team (Luden, JAP, 2011). We performed full physiological and performance profiles (including muscle biopsies) at 1) the start of the season, and 2) before, and 3) after a 3 week taper (leading up to Conference Championships).

The results:

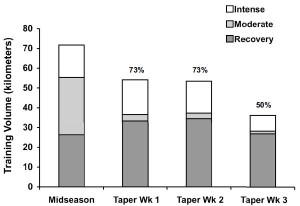

Without any specific instructions, the athletes chose to implement a step-taper, hitting the 50% mark (which equated to ~25 miles) by week 3 (Figure 2). Interestingly, they got there almost exclusive by removing “moderate intensity” work. As expected, this reduced mileage did not alter their VO2max! Nor did it compromise their race-pace running economy (i.e., metabolic efficiency). They also maintained their pre-taper aerobic enzyme (Citrate Synthase) concentrations. This all is matched our pre-study hypotheses.

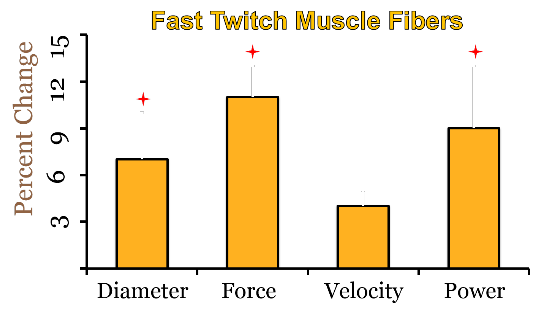

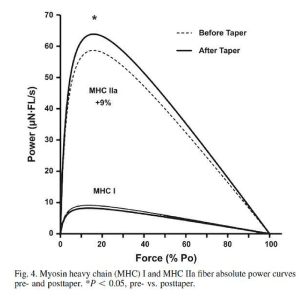

What blew us away were the changes of the single muscle fiber function. We studied hundreds of individual muscle fibers (per subject), scrutinizing their size, fiber-type, and contractile properties. One by one, we tied them to mini force transducers while lying in a bath of salt, Calcium, and ATP. This allowed us to assess the maximal contractile properties of each fiber, independent of any neurological, metabolic, energetic, or connective tissue contributions. We found that during taper, the fast-twitch muscle fibers (MHC IIa) INCREASED their maximal power by 9%!

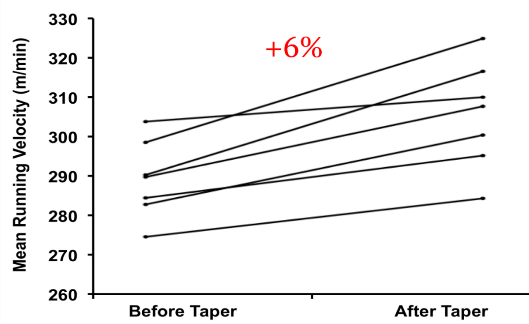

Fast-twitch fiber size (~7%) and strength (~12%) also significant increased (Figure 4). Translation: these runners got bigger, stronger, and more powerful at the single muscle cell level during 3 weeks of REDUCED running volume. Most importantly, every single runner improved their race performance, with an average performance boost of 6%. This was particularly impressive given the post-taper race occurring over a significantly greater change in elevation and was ran into a headwind!

Conclusion:

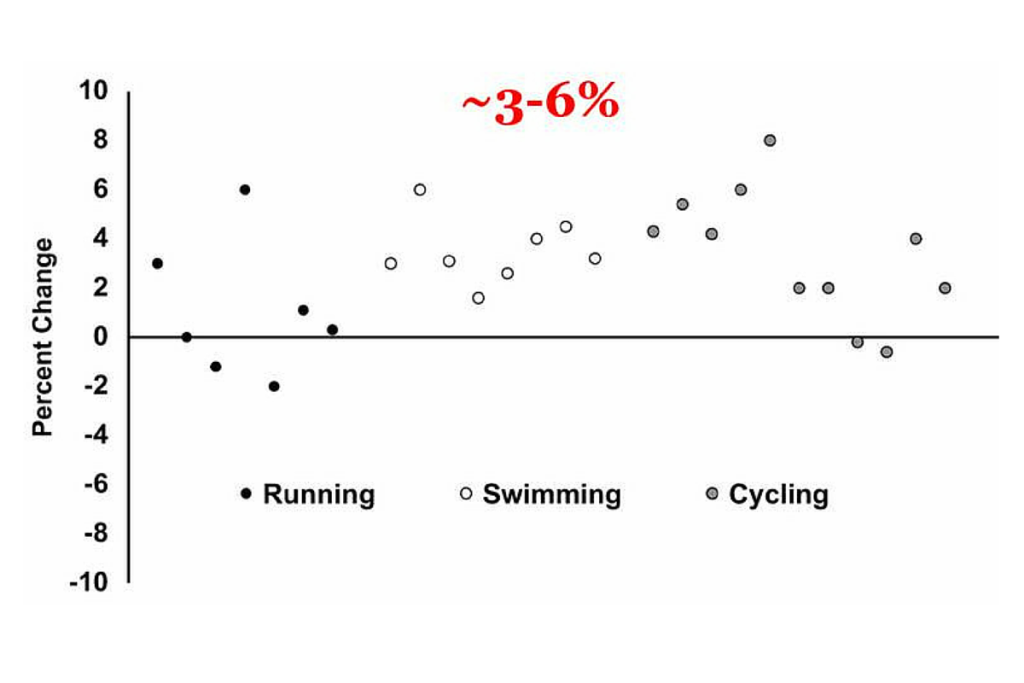

The scientific efficacy of a well-designed taper is unquestionable. A review of the research on tapering for endurance sports suggests a general improvement in performance of ~3-6% (Figure 5 – each dot represents a unique, peer-reviewed study). Keep in mind, in the 2000 Olympics, the difference between a gold medal and 4th place was just 1.62%.

Andy Galpin, PhD Human Bioenergetics

www.BarbellUniversity.com

Twitter & Instagram : @DrAndyGalpin

References:

1. Luden N, Hayes E, Galpin AJ, Minchev K, Jemiolo B, Raue U, Trappe TA, Harber MP, Bowers T, and Trappe SW. Myocellular basis for tapering in competitive distance runners. Journal of Applied Physiology. Jun; 108(6): 1501-9.

2. Mujika L, and Padilla S. Scientific bases for precompetition tapering strategies. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. Jul; 35(7): 1182-7.